It’s not unusual to find fairy tales or folk tales that have been reinvented or brought up to date in SF&F these days; Neil Gaiman’s Anansi Boys is probably one of the best-known examples of this particular trope. But in Big Mama Stories, Eleanor Arnason, known for anthropological SF stories like A Woman of the Iron People, has created a batch of new folk tales for the twenty-first century, with an entirely new cast of mythic characters. The results are reminiscent of Stanislaw Lem’s Cyberiad or Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics: witty and fanciful short stories, populated with fantastical beings having larger-than-life adventures. Her prose has the straightforward quality of a good campfire story, and her characters are a delight.

Arnason’s Big Mamas—a varied, good-natured, formidable crew of galaxy-sized women—descend from the folkloric lineage of characters like Paul Bunyan and trickster figures like Coyote. They are powerful beings who can travel through time by sheer force of character; they can wander the vacuum of space or pass for ordinary human beings; they come in all kinds of colors, and they survive by their wits. There are even Big Mama equivalents in alien species, like the insectoid alien Zk Big Mama and the Skwork Large Parent. They are practical as only long-lived time-traveling entities can be; each is “a child of the universe and not always kind, though [they] try to step softly among the stars and do more good than harm.” There are Big Poppas too, although they don’t enter into the stories as much. They’re certainly not needed to come to the rescue of any of the Big Mamas in “Big Black Mama and the Tentacle Man,” in which the Big Mamas put a Cthulhoid nasty in his place with ease.

Elsewhere, Big Mamas cross paths with the smaller-scale sentients of the universe, with all manner of results. Big Ugly Mama must use time-travel to try and fix a mistake with an alien from the Zk race, while later Big Red Mama has to sort out the problems that result when a human figures out how to build a time machine. An attempt by Big Green Mama to cure her own loneliness by dividing herself in two brings her (and her double, and her double’s doubles) into the aftermath of a biological war in which the participants discovered that microbes and viruses are not very good at recognizing national boundaries.

“Big Brown Mama and Brer Rabbit” is the longest story and is much more in keeping with the Anansi Boys style of folktale reinvention, envisioning the trickster Brer Rabbit as an archetype of African-American migration from the South into the industrial cities of the North. Disguised in a man-suit made of red clay and railroad grease, Brer Rabbit leaves the weevil-ravaged cotton fields to work for the Ford Motor Company in Detroit, eventually encountering Big Red Mama in Minneapolis, who recognizes him for what he is. Arnason’s didacticism gets the better of her here, as Brer Rabbit’s narration of his life sometimes reads like a history lesson. But there’s a delightful inventiveness in his meeting with the Ojibwe figures of Nokomis and Nanabozho, who become his allies and close friends, and the vision of the future Arnason invents here is beautifully hopeful and diverse.

Arnason’s Big Mama mythos is a highly enjoyable and strongly feminist synthesis of science, history, and sheer imagination. Like the best fairy tales and folk tales, her stories sometimes go to dark and unsettling places, but they’re really about how to overcome the darkness—how to take a long view of the universe, where individual lives are at once very small but also very important and precious.

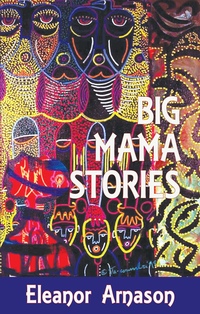

Big Mama Stories is available now from Aqueduct Press.

Karin Kross lives and writes in Austin, TX. She can be found elsewhere on Tumblr and Twitter.